What are tariffs and why do we need them?

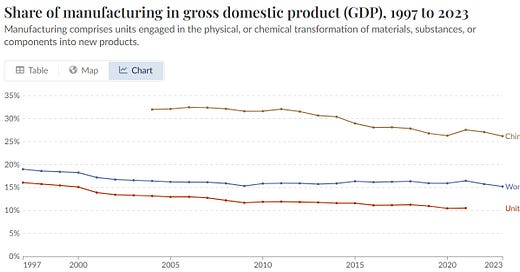

Tariffs are a domestic tax placed on goods and services imported from foreign countries. Recently tariffs have been in the news due to President Donald Trump’s confusing, inconsistent, and frankly erratic policy and rhetoric regarding trade deals and tariffs. But, as with many things, in the core of President Trump’s message there is a kernel of truth, and that is; in the past many countries have used tariffs to protect nascent or developing domestic industries in the face of foreign competition. The United States was once one of the most industrious nations in the world, but while our GDP continued to grow over the latter half 20th century, our industrial base withered while we shifted from an industry-based economy to a service-based economy. Tariffs, though not as the current administration has implemented them, can remedy this and help to rebuild American manufacturing.

Critiques and Concerns

Economists, political analysts, and the common man alike have many criticisms and concerns about the implementation of tariffs. It’s reasonable to worry about tariffs, they are after all a tax. Consumers worry about the prices of goods, economists worry about the impact on growth, and political analysts worry about maintaining relations with foreign countries. Each of these concerns are real, reasonable, and completely rational, but if the United States is to rebuild its manufacturing base tariffs are a necessary step.

Drawn from these concerns, critics offer three primary challenges to the implementation of tariffs. The first and most fundamental argument is that the United States does not need to or should not try to re-industrialize. Others argue that tariffs would fail to create sufficient incentives to re-industrialize, they will only raise prices. Finally, others argue that while tariffs could be used to boost American manufacturing, other economic interventions like subsidies, tax cuts, or deregulation are preferable to tariffs and are capable of similarly boosting American industry. Each of these critiques has merit, and while they're all worth consideration, they all fail to consider the question of tariffs and re-industrialization in its entirety.

Addressing the Criticisms

America does not need to re-industrialize.

The United States economy is large, healthy, and nominally stable, but it relies heavily on foreign countries, and notably foreign adversaries, for multiple necessary components of modern society. About 80% of all n active pharmaceutical ingredients in the U.S. are purchased from China and 97% of all antibiotics in the U.S. come from China. The United States once produced enough Rare Earth Elements to be self-reliant, and as of 2013 the United States has become 100% reliant on imported REEs which are imported primarily from China. Taiwan produces more than 50% of the world’s semiconductors, and while they are an American ally they are under constant threat of conflict with China. While it may be unreasonable to suggest that the United States must be 100% self-reliant for every good and service consumed within its borders, it is clear that there are several key industries in which the U.S. is too reliant on foreign producers such that it would be crippled if access to them would be cut off.

Tariffs will not spur re-industrialization.

Tariffs and other trade barriers have been used historically by multiple countries, including the U.S., Japan, United Kingdom, and France, to build nascent industries with varying degrees of success. While tariffs will be accompanied by price increases, they are useful tools to strengthen infant industries.

Other methods are preferable to tariffs to re-industrialize the United States.

Subsidies, tax cuts, and de-regulation are all great tools for promoting domestic investment and growth, but they miss out on the fact that other nations will still have tariffs on the United States. The United States has one of the lowest average tariff rates in the world. If the United States has lower tariffs on foreign goods than foreign countries have on us, then foreign countries will have an advantage when entering our market compared to American producers trying to enter there. So, unless subsidies, tax cuts, and de-regulation can reduce the price of manufacturing in the U.S. such that it offsets the cost of producing in foreign markets American companies will continue to choose to produce in foreign markets rather than the domestic one. While tariffs do not (directly) change the cost of producing domestically, they do effectively increase the cost of producing in foreign countries, hopefully encouraging a shift toward domestic production.