There has been a long interest in those who identify as religious nationalists everywhere about the idea of creating a government based on what that group believes is the national religious values. Theocracy is defined by Mr. Ross Douthat from his article Theocracy, Theocracy, Theocracy as — “The word is often used to connote government by a specific institutional faith — Shia imams in Iran, say, or Wahhabi clerics in Afghanistan — with the clergy writing laws and a temple guard enforcing them.” In essence, a national government ruled by religious interests or by a particular sect of a religion. Iran, being the most notable modern example after the 1970s Iranian Revolution where zealous extremists followed Ayatollah Khomeini into government after the disposal of the Shah Government. In the United States, it is more oppositely identified with by Evangelistic Christians and Conservative leaning individuals. Pew Research discussed this in a recent October 2022 survey where they found that:

Three-quarters of Republicans (76%) say the founders intended for the U.S. to be a Christian nation, compared with roughly half of Democrats (47%). Republicans also are at least twice as likely as Democrats to say that America should be a Christian nation (67% vs. 29%) and that the Bible should have more influence over U.S. laws than the will of the people if they conflict (40% vs. 16%).

While this survey states these findings, almost two-thirds claim different meanings to the definition. Let’s simplify that it means theocracy holds three premises: 1) the majority or totality of government is controlled by one sect or religion. 2) that same group dictates the values or moral laws of said government. Lastly, 3) said group also dictates their religion as the national faith of their country. Kevin Phillips in his book American Theocracy simplifies it as “some degree of rule by religion.” Phillips’ book ascribes some tenets of theocracy as: cultural antimodernism, warhawkishness, conservative fundamentalism, and a demand for governments by literal biblical interpretation. The basis for Christian Theocracy in America has been described as coming from the pursuit of individualistic faith sects that promoted a personal relationship with God, as well as an almost ‘imperial’ or ‘expansionist’ sentiment that came later within the American South during the Dixie Era when the South believed it was its divine right to manifest westward in competition to Northern states, and much more recently in the Civil Rights Era when southern Dixiecrats sought to uphold the “old order of things” in contrast to Republican Reconstruction and the later push for Civil Rights legislation (described in Charles Dew’s book Apostles of Disunion). The overall ideology stems from southern-regionalism spread through the U.S. en-masse by evangelists like Billy Graham in the twentieth to early twenty-first centuries. The sense of fundamentalism is described in Fundamentalisms Observed by Marty and Appleby as, “[they] arise in times of crisis, real or perceived…the ensuing crisis is perceived as a crisis of identity by those who fear extinction.”

The proponents of theocracy generally see it as more embracing and the preservation of traditionalism, national values, and mostly, the preservation of an identity. Phillips makes the sentiment numerously in his book that this is usually a nation’s last manifestation of its power or identity, because it has lost any other avenue to express itself. The touting of religion is usually the last phase in a nation’s identity, and as he mentions, has ironically played a role in the death of four great empires: Rome, Britain, Spain, and the Dutch.

Critics of this system hold the following tenets: 1) a growing concern for economic, social, or political decay. 2) growing religious fervor or fundamentalism or collusion between church and state. 3) growing reliance on faith alone over rationalism, science, and innovative reason produced by the enlightenment era. 4) growing sense of sedentary nature as those individuals believe the great revival lies in the coming of Christ, this has historically led to a stagnation of progress, innovation, business, and other key factors according to Phillips and other authors.

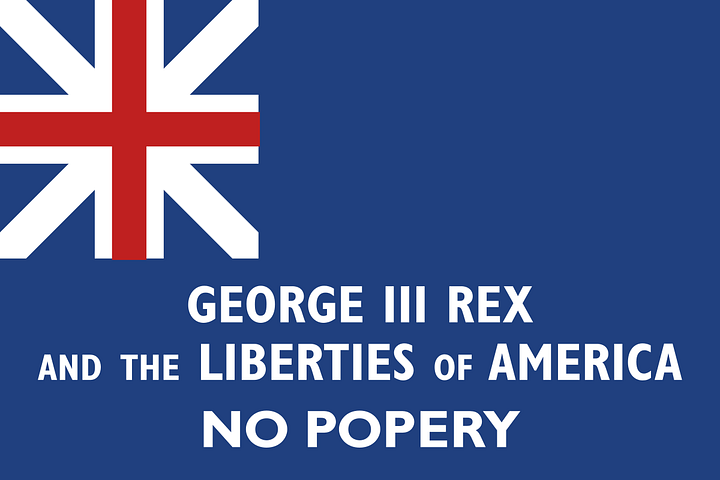

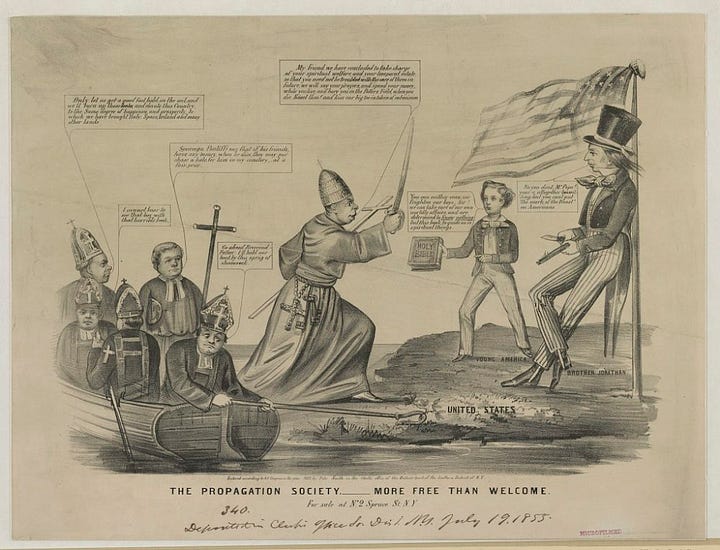

If one looks at the fervor of those proponents it can be argued this militance creates some dangerous antidemocratic principles in a national religious movement: the ideas of supremacy as with the Antebellum South and Civil Rights Era, militant distrust or discrimination to other groups like Muslims as with post-9/11 and even with other Christian groups like anti-Catholicism from the foundation to the 1960s with the election of JFK, and these senses of religious zealousness and the idea every denomination believes their way is the right one produces an eternal conflict among groups, or can result in (as the U.S. is a majority protestant country) majority rule over others seen as setting-back the movement. As colleague writer Sean Goins writes on in critique of theocracy’s outcomes;

“Christian nationalism, in its quest to mold America into a theocracy, embodies this very stagnation. It demands not a nation of strong, free-thinking individuals but docile believers who fear questioning doctrine.”

There may be some good pros to theocracy to those who argue for it, but also, plenty of great arguments against it in the eyes of critics. However, perhaps the best theocracy is just as good a government as the best dictatorship, best oligarchy, or the best autocracy.